The year 2014 was a great one for old school gaming.

5e D&D, which I've run with some success, isn't an old school game, and even if it hadn't been released, it would still have been an excellent year for the old school. It's a reasonably good game that plays pretty close to how most of us played 2nd edition AD&D in the 1990s, with some tweaks from the 3e and 4e eras. Old school material is being published for 5e, including OSR authors going and adapting or creating material. It's all to the good; we need D&D to keep fresh blood coming in, and it's better to have a good edition than a bad one.

The overachiever in 2014 is Lamentations of the Flame Princess. The fact that the Free RPG Day adventure was nowhere near as good as last year's doesn't diminish at all the sheer volume of excellent output that LotFP had this year.

Releasing two modules as solid as Forgive Us and Scenic Dunnsmouth in a year would be more accomplishment than most publishers have in a year. The former is a work of art in presenting a module using only two-page spreads, while the latter puts the die-drop area generation method to good use. But then the December releases came out.

Again, just releasing a solid island adventure like The Idea from Space or an absolutely alien concept sandbox like No Salvation for Witches would also be a triumph. The two are seriously great high-concept modules, with NSFW probably taking the edge. And the December releases included great reissues of Tower of the Stargazer and Death Frost Doom. But they are all dwarfed by A Red & Pleasant Land.

RPL is Zak S's book based on Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and, to some degree, Dracula. Rather than adapt these works to things already handled by D&D type gaming, it presents a way to adapt D&D type gaming to a bloodthirsty Eastern European land of madness. The book is packed with game-useful stuff, every bit of which is a challenge to the rote standard fantasy that predominates in the RPG industry. The book is a gauntlet thrown down to less imaginative concepts of what D&D can be, and it even has rules for dueling. (But you need to have a glove.)

LotFP has a heap of ambition for next year. Aside from the Referee Book, which I hope will be coming out next year, there are another half-dozen plus adventures and sourcebooks that are bursting with more amazing promise. Including the long-awaited follow-up to Carcosa by Geoffrey McKinney.

So what can compete with that? Goodman Games has been trying. They haven't released anything as revolutionary as RPL, but they have been doing some great stuff in publishing, most of it supported by Kickstarters. The KS for The Chained Coffin, an adventure set in a fantasy Appalachia written by Michael Curtis, turned into a deluxe boxed set that puts out a full setting worth of material. They wound up doing another KS that resulted in a similar treatment for Perils on the Purple Planet by Harley Stroh. This one is a sword & planet module.

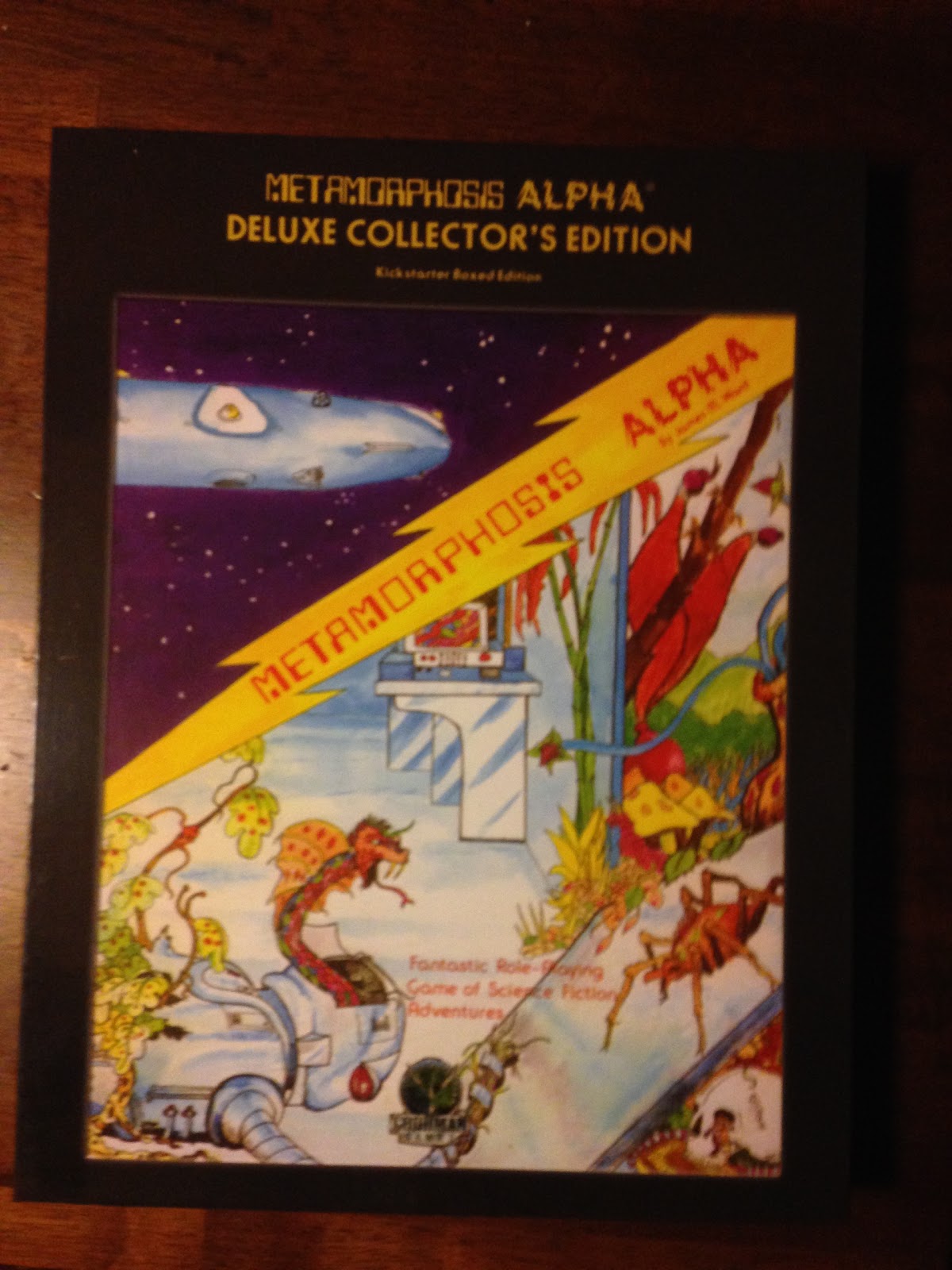

Not to mention - Goodman did another Kickstarter for Metamorphosis Alpha that is suddenly turning it into a supported product line (you can see the line-up here). Just the special edition book is a terrific collection; the final result should make fans of MA jump up and down in celebration. Goodman's next deluxe edition will be of Grimtooth's Traps – the classic collection of Rube Goldberg traps that go over the top to slay the party.

Goodman is also releasing 5e modules. These are serviceable, but not much more; it's disappointing, when so much good stuff is going on in other areas, that they went pedestrian at a time when greatness was called for.

Basic Fantasy RPG has kept on keepin' on This year saw several new print releases: Adventure Anthology 1, BFRPG Third Edition, and The Basic Fantasy Field Guide (a monster expansion). BFRPG has always been a labor of love, and where Lamentations and DCC are trying to do revolutionary things and present mind-blowing ideas, BFRPG presents the unvarnished real stuff of classic D&D. If you want a game that is steeped in the "classic" fantasy feel of '80s D&D, Basic Fantasy delivers exactly that.

The Adventure Anthology is a total mixed bag, of course, but it does offer good bits if you need to run D&D for a session. The Field Guide is fine, and is a mixed bag of monsters that needed to be adapted to BFRPG and innovative new creatures. There's going to be a new edition of BF1 Morgansfort coming shortly, which will update some of the adventures in that collection. Basic Fantasy has always tinkered with its older material, and in a certain sense it has become a distillation of the old religion of D&D.

Labyrinth Lord has been in a weird place for several years now. It's still the system of choice for megadungeons, and when the unbelievable happened and Dwimmermount was released earlier this year, it was for Labyrinth Lord and then ACKS. But Labyrinth Lord is more or less a shorthand for "yeah, this is compatible with B/X D&D" and has very much not been taking the lead in driving things forward. It's entered the long tail.

OSRIC never really wasn't in the long tail; its main purpose has always been to keep publishing 1e AD&D modules. It's kept that happening; if nobody else will, & Magazine and Expeditious Retreat Press will keep new material going for as long as the 1e grognards are around.

Adventurer Conqueror King has been absolutely slammed by Dwimmermount. It caused a big stir when it was released, but it has really only had three significant releases since then: the Player's Companion, Domains at War and Dwimmermount. Of course, you could buy those and not need anything else for the next two years of gaming – so who's going to complain?

Swords & Wizardry is in an even weirder place. There is plenty of Swords & Wizardry material coming out from Frog God Games. Most of it is fine and old school in spirit – but it's all basically adaptations of Pathfinder products, and now Necromancer Games's 5e products. That was true before this year, but it's really become the main stream of new S&W material. Which means that it's more or less a side option for existing publishers, frankly.

There are plenty of other clones, but I think these are the ones driving most of what we see today in the old school gaming scene. It's not that I don't like Delving Deeper, or Seven Voyages of Zylarthen, or BLUEHOLME, but they're serving a niche of a niche.

One area where it's absolutely thriving are zines. Aside from James Maliszewski's Tékumel zine The Excellent Travelling Volume and long-running system neutral zines like Scott Moberly's AFS or Tim Shorts's The Manor, the games that are killing it with excellent zines aren't really that surprising.

Dungeon Crawl Classics: Crawl!, Metal Gods of Ur-Hadad, Crawljammer, Crawling Under a Broken Moon

Lamentations of the Flame Princess: The Undercroft, Vacant Ritual Assembly

It's hard to say what will happen in the future, but the momentum really seems to be with LotFP and DCC RPG. I see them as continuing to be the driving force. What would make 2015 an even greater year is if another publisher takes up the gauntlet that LotFP has thrown and tries to put out products that are as heavy on utility and as fresh in ideas.

Tuesday, December 30, 2014

Saturday, December 27, 2014

Actual Play: Running Metamorphosis Alpha

Since I have time off over the holidays, I wanted to make sure I got at least one really prime game in, and for months I've been wanting that to be Metamorphosis Alpha. So I finally got that done today, and a game has gone right from my to-play list to the list of games I really enjoy.

I had no idea what MA would actually be like in play, but Tim Kask's introduction to the new Goodman Games edition really defined some of the delightful moments: it gets a bit into cultural anthropologists as you explain high-tech things to players like they're the tribal barbarians their player characters are meant to be.

I loved mixing this with known science, which I think is why so many Gamma World games went into "modern plus apocalypse" rather than the "future plus apocalypse" that it was supposed to. I mean, an iPhone is basically a strange rectangle where one side is glass and the other is metal, and it has one button. (And when a PC pressed the button, an icon displaying no battery power came up. Familiar to anyone?)

The random Round House Modular Dwelling Unit generator in Craig J. Brain's module The House on the Hill helped generate some priceless moments. I think the players really enjoyed the discovery process with a packet of salt & vinegar potato chips that came out of the food machine and were a theme for the rest of the adventure. The RHMDU is a brilliant place to explore; the PCs actually got into the administrative center for a bit because of a laser pistol they had found.

Brian Blume's bionics (reproduced in the Goodman edition) made a really threatening NPC who got offed with the laser pistol - it did him a ton of damage, even more than he did with his bionic arm and vibro-sword. And I wound up using Jim Ward's forest level from Dungeoneer (also in the Goodman tome) when the PCs left the confines of the level I had designed. Both the Goodman book and House on the Hill pulled their weight.

One detail I really enjoyed playing out was that the PCs, in the RHMDU, found "casual clothing" - which I decided had them going around in "Starship Warden" t-shirts. I might need to petition WardCo to actually make some because I'm just so tickled by the idea. I also enjoyed the PCs finding out that the radiation-riddled "Forbidden Zone" was really, well, forbidden and not just somewhere the PCs' parents had warned them against.

The session ended in disaster because the PCs found explosives, which I described pretty clearly as C4. I know, I could've gone with something else, but it's so much more fun to run with something you can really get into describing. Plus, there's electrical effects abound in the game, and given that C4 is activated by electricity it only seemed fitting. This was what did the PCs in, as the electrified shed in the Dungeoneer level and a PC's ability to generate electricity both combined with the C4 and blew the PCs and the shed to kingdom come. (Two PCs technically survived because, as a G+ Hangout game, their players dropped out before the grand finale.)

The ending was appropriate given that it was a one-shot; I see MA as perfect for one-shots, or maybe a "mini-series" planned campaign. It was based on novels which are fairly brief, and relies heavily on the theme of discovery. I could also very much see it blending into D&D as I discussed in my last post. Because it isn't class-and-level based, players can get to the really good stuff right in their first or second adventure, and don't need to go through a grind of level building.

It deserves some mention that the system is more rough hewn than even OD&D. The organization of the rulebook is awful, especially given that the WardCo and Goodman reprints both contain errata-ed versions of most of the essential tables that you use to run the game. (And don't get me started on the fact that the mutations are in basically arbitrary order.) The lacunae don't really matter much, though, because the system is simply so light that an experienced referee can just make a ruling and not change the game at all. The material that is present works quite well, but it's not a game to be run by a neophyte.

One hint for the prospective referee: you should have stats for any NPCs or monsters you're using. The game runs a lot more smoothly when, at a minimum, they have Mental Resistance and Dexterity scores, and at that point you might as well give them Constitution, Strength and Radiation Resistance.

Metamorphosis Alpha is going through the best period of support in its lifetime, thanks to Goodman Games and WardCo. It's very different from the D&D experience, but it is really worth giving a try in play. MA is really good for gamers who've played a lot of D&D and want the excitement of fresh discovery, really specializing in that aspect of play, and because of how it's structured it doesn't require a commitment of months or years to a campaign.

I had no idea what MA would actually be like in play, but Tim Kask's introduction to the new Goodman Games edition really defined some of the delightful moments: it gets a bit into cultural anthropologists as you explain high-tech things to players like they're the tribal barbarians their player characters are meant to be.

I loved mixing this with known science, which I think is why so many Gamma World games went into "modern plus apocalypse" rather than the "future plus apocalypse" that it was supposed to. I mean, an iPhone is basically a strange rectangle where one side is glass and the other is metal, and it has one button. (And when a PC pressed the button, an icon displaying no battery power came up. Familiar to anyone?)

The random Round House Modular Dwelling Unit generator in Craig J. Brain's module The House on the Hill helped generate some priceless moments. I think the players really enjoyed the discovery process with a packet of salt & vinegar potato chips that came out of the food machine and were a theme for the rest of the adventure. The RHMDU is a brilliant place to explore; the PCs actually got into the administrative center for a bit because of a laser pistol they had found.

Brian Blume's bionics (reproduced in the Goodman edition) made a really threatening NPC who got offed with the laser pistol - it did him a ton of damage, even more than he did with his bionic arm and vibro-sword. And I wound up using Jim Ward's forest level from Dungeoneer (also in the Goodman tome) when the PCs left the confines of the level I had designed. Both the Goodman book and House on the Hill pulled their weight.

One detail I really enjoyed playing out was that the PCs, in the RHMDU, found "casual clothing" - which I decided had them going around in "Starship Warden" t-shirts. I might need to petition WardCo to actually make some because I'm just so tickled by the idea. I also enjoyed the PCs finding out that the radiation-riddled "Forbidden Zone" was really, well, forbidden and not just somewhere the PCs' parents had warned them against.

The session ended in disaster because the PCs found explosives, which I described pretty clearly as C4. I know, I could've gone with something else, but it's so much more fun to run with something you can really get into describing. Plus, there's electrical effects abound in the game, and given that C4 is activated by electricity it only seemed fitting. This was what did the PCs in, as the electrified shed in the Dungeoneer level and a PC's ability to generate electricity both combined with the C4 and blew the PCs and the shed to kingdom come. (Two PCs technically survived because, as a G+ Hangout game, their players dropped out before the grand finale.)

The ending was appropriate given that it was a one-shot; I see MA as perfect for one-shots, or maybe a "mini-series" planned campaign. It was based on novels which are fairly brief, and relies heavily on the theme of discovery. I could also very much see it blending into D&D as I discussed in my last post. Because it isn't class-and-level based, players can get to the really good stuff right in their first or second adventure, and don't need to go through a grind of level building.

It deserves some mention that the system is more rough hewn than even OD&D. The organization of the rulebook is awful, especially given that the WardCo and Goodman reprints both contain errata-ed versions of most of the essential tables that you use to run the game. (And don't get me started on the fact that the mutations are in basically arbitrary order.) The lacunae don't really matter much, though, because the system is simply so light that an experienced referee can just make a ruling and not change the game at all. The material that is present works quite well, but it's not a game to be run by a neophyte.

One hint for the prospective referee: you should have stats for any NPCs or monsters you're using. The game runs a lot more smoothly when, at a minimum, they have Mental Resistance and Dexterity scores, and at that point you might as well give them Constitution, Strength and Radiation Resistance.

Metamorphosis Alpha is going through the best period of support in its lifetime, thanks to Goodman Games and WardCo. It's very different from the D&D experience, but it is really worth giving a try in play. MA is really good for gamers who've played a lot of D&D and want the excitement of fresh discovery, really specializing in that aspect of play, and because of how it's structured it doesn't require a commitment of months or years to a campaign.

Thursday, December 18, 2014

Mashup: Holmes D&D and Metamorphosis Alpha

I love the Holmes rulebook, and I often wonder why I have so much affection for it. Part of it is simply that Dave Sutherland cover; the art is not polished but it is completely evocative, both in color and in the monochrome blue. (I particularly love the blue book look.)

But it's the potential in the incomplete work that draws me in. The Holmes booklet allows the DM to run a few games of D&D, but not a full campaign. Meepo's Companion is an easy fix, and fills out levels 4 through 9 in just four pages. From that basis, unorthodox "supplements" to the Holmes rulebook are one of my favorite thought experiments. It allows you to have a basis that is 100% classic Dungeons & Dragons, but change everything outside that core and create something totally different.

Of course, it helps that TSR published something totally different from D&D just a year before Holmes Basic. Just re-released as a super-deluxe book by Goodman Games, Metamorphosis Alpha is a wild game of exploration in a generation starship that has gone horribly wrong. Radiation killed most of the people on board, and the survivors have reverted to barbarism. There are weird animal mutants, deadly plants and high-tech weapons and gadgets abounding in the setting. It's a decided alternative to the stereotypical post-nuclear apocalypse world that, for instance, appears in Jim Ward's later Gamma World. MA gives nigh-magical powers through mutations, and cares not for hard science.

The games are both focused on exploration, and as such make a natural pairing. The mutants and high technology of MA are excellent variants on the overly-familiar fantasy tropes supported in Dungeons & Dragons, while D&D's framework is fundamentally similar to MA's, to the point where MA has been called a "megadungeon in space." And while MA has some wild and awesome ideas, D&D is more of a sustainable campaign game.

MA's system is very nearly in scale with classic D&D, and uses similar systems of armor, weapon, and hit dice. Its characters don't advance, and get hit points as a direct function of Constitution (1d6 per point). This is similar to an eighth level D&D fighting-man using the Holmes Companion, so it stands to reason that the tougher MA creatures will be at the lower dungeon levels, with only a scattering of mutants in the first levels. Jim Ward's game is notoriously tough, and even with D&D levels and spells it's still not a walk in the park.

Look at the Tom Wham "Skull Mountain" dungeon layout:

This is a perfect fit for a D&D/MA mashup. I picture the early levels being fairly straightforward D&D type affairs, with hints of more – a stray mutant or two, a piece of inexplicable technology here and there. Then level 4A is the first level with serious numbers of Metamorphosis Alpha style mutations as well as D&D monsters, while 4B focuses on some of the tougher "fantasy" baddies. Then the 5th and 6th levels have some serious high-tech artifacts as well as some of the humanoid mutations of MA, and progressively meaner creatures. Finally the 7th level - the "Domed City" - is a high tech city straight out of Metamorphosis Alpha. A twist suggested by Zach H of Zenopus Archives is to have the whole of Skull Mountain be aboard MA's Starship Warden.

I like this setup because it takes TSR's two "lightest" rulesets, and links them together in what I feel is a largely organic way. For instance, it would be perfectly fun to have PCs roll up a Radiation Resistance score the very first time they actually encounter radiation. Mental Resistance can be converted from Wisdom, and Leadership from Charisma. And it merges the "big reveal" style of MA with the "secret at the heart of the dungeon" aspect that D&D always promises but it turns out to be a chute to China.

(If you read that link, or if you know your classic Dragon magazines, you know that Gygax did send PCs to the Warden; here we are talking about the opposite, using MA as the "reveal" at the deeper levels of D&D.)

The mashup has some great potential for chocolate/peanut butter type mixtures. First, factions in a large-scale dungeon transition naturally into some of the classic MA bad guys: wolfoids and androids, particularly, are classic MA villains. Technology, particularly Brian Blume's Bionics table from The Dragon (Jeff Rients reproduced it here) could be a lot of fun when applied to D&D monsters. Imagine a hobgoblin with a bionic arm, or a hyper-intelligent ogre with bionic eyes and brain. Mutations, too – I mean, come on, you can have kobolds that fire frickin' lasers from their eyes. Meanwhile the D&D magic items gain particular effect in MA; after all, think of the power of a single Ring of Animal Control over the mutated beasts of MA. Not to mention the visual of, say, a bearoid wielding a flaming sword.

Part of why I think I'm enjoying this particular blend of sci-fi and fantasy over the more sword and planet ideas I've explored in the past is that it's a very human-centric game, and rooted firmly in RPG history. It also lives up to the sci-fi elements that were present in the original edition of D&D but disappeared shortly thereafter. I like it enough that I think it's worth pursuing further and looking at some of the places where the two games intersect in the most interesting ways.

But it's the potential in the incomplete work that draws me in. The Holmes booklet allows the DM to run a few games of D&D, but not a full campaign. Meepo's Companion is an easy fix, and fills out levels 4 through 9 in just four pages. From that basis, unorthodox "supplements" to the Holmes rulebook are one of my favorite thought experiments. It allows you to have a basis that is 100% classic Dungeons & Dragons, but change everything outside that core and create something totally different.

Of course, it helps that TSR published something totally different from D&D just a year before Holmes Basic. Just re-released as a super-deluxe book by Goodman Games, Metamorphosis Alpha is a wild game of exploration in a generation starship that has gone horribly wrong. Radiation killed most of the people on board, and the survivors have reverted to barbarism. There are weird animal mutants, deadly plants and high-tech weapons and gadgets abounding in the setting. It's a decided alternative to the stereotypical post-nuclear apocalypse world that, for instance, appears in Jim Ward's later Gamma World. MA gives nigh-magical powers through mutations, and cares not for hard science.

The games are both focused on exploration, and as such make a natural pairing. The mutants and high technology of MA are excellent variants on the overly-familiar fantasy tropes supported in Dungeons & Dragons, while D&D's framework is fundamentally similar to MA's, to the point where MA has been called a "megadungeon in space." And while MA has some wild and awesome ideas, D&D is more of a sustainable campaign game.

MA's system is very nearly in scale with classic D&D, and uses similar systems of armor, weapon, and hit dice. Its characters don't advance, and get hit points as a direct function of Constitution (1d6 per point). This is similar to an eighth level D&D fighting-man using the Holmes Companion, so it stands to reason that the tougher MA creatures will be at the lower dungeon levels, with only a scattering of mutants in the first levels. Jim Ward's game is notoriously tough, and even with D&D levels and spells it's still not a walk in the park.

Look at the Tom Wham "Skull Mountain" dungeon layout:

This is a perfect fit for a D&D/MA mashup. I picture the early levels being fairly straightforward D&D type affairs, with hints of more – a stray mutant or two, a piece of inexplicable technology here and there. Then level 4A is the first level with serious numbers of Metamorphosis Alpha style mutations as well as D&D monsters, while 4B focuses on some of the tougher "fantasy" baddies. Then the 5th and 6th levels have some serious high-tech artifacts as well as some of the humanoid mutations of MA, and progressively meaner creatures. Finally the 7th level - the "Domed City" - is a high tech city straight out of Metamorphosis Alpha. A twist suggested by Zach H of Zenopus Archives is to have the whole of Skull Mountain be aboard MA's Starship Warden.

I like this setup because it takes TSR's two "lightest" rulesets, and links them together in what I feel is a largely organic way. For instance, it would be perfectly fun to have PCs roll up a Radiation Resistance score the very first time they actually encounter radiation. Mental Resistance can be converted from Wisdom, and Leadership from Charisma. And it merges the "big reveal" style of MA with the "secret at the heart of the dungeon" aspect that D&D always promises but it turns out to be a chute to China.

(If you read that link, or if you know your classic Dragon magazines, you know that Gygax did send PCs to the Warden; here we are talking about the opposite, using MA as the "reveal" at the deeper levels of D&D.)

The mashup has some great potential for chocolate/peanut butter type mixtures. First, factions in a large-scale dungeon transition naturally into some of the classic MA bad guys: wolfoids and androids, particularly, are classic MA villains. Technology, particularly Brian Blume's Bionics table from The Dragon (Jeff Rients reproduced it here) could be a lot of fun when applied to D&D monsters. Imagine a hobgoblin with a bionic arm, or a hyper-intelligent ogre with bionic eyes and brain. Mutations, too – I mean, come on, you can have kobolds that fire frickin' lasers from their eyes. Meanwhile the D&D magic items gain particular effect in MA; after all, think of the power of a single Ring of Animal Control over the mutated beasts of MA. Not to mention the visual of, say, a bearoid wielding a flaming sword.

Part of why I think I'm enjoying this particular blend of sci-fi and fantasy over the more sword and planet ideas I've explored in the past is that it's a very human-centric game, and rooted firmly in RPG history. It also lives up to the sci-fi elements that were present in the original edition of D&D but disappeared shortly thereafter. I like it enough that I think it's worth pursuing further and looking at some of the places where the two games intersect in the most interesting ways.

Labels:

holmes,

mashup,

metamorphosis alpha,

science fantasy

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

Initiative, Dexterity and Ready Ref Sheets

The title of this blog is Macaronic Latin for "Always Initiative One," but I don't actually write about initiative much. Which is odd, because I actually do think about it a good bit, just not in a format that's ready to write about. Here I'm going to be focusing on OD&D, although coming at it by way of Chainmail.

In the first round of Chainmail man-to-man, the attacker strikes first, unless the defender has a longer weapon, or the defender has high ground. In subsequent rounds, initiative stays the same, unless one side has a shorter weapon or the high ground. All of this makes sense. If a man with a sword attacks a man with a spear, the spear-wielder can fend him off and get the first blow in, but if they both survive, the man with the sword has the advantage because he's overcome the spear's range and can work more quickly.

The state of affairs in Chainmail is good, and it's worth seeing what we can do in terms of replicating it in D&D. Unfortunately, it doesn't cover enough possibilities; what if someone is firing missiles, or throwing spells, or fighting against a creature that attacks with its claws? Chainmail only has 12 weapon types (if you don't have Chainmail but do have OD&D or Holmes Basic, the weapons are arranged in order by length in both of those books). So clearly it's going to need some work.

Outside of surprise, the main comment that OD&D has on initiative is under the description of abilities:

Dexterity applies to both manual speed and conjuration. It will indicate the character's missile ability and speed with actions such as firing first, getting off a spell, etc.We're not told how Dexterity indicates this. We can compare stats when an Elf is taking a shot at an Evil High Priest, to see whether the Elf's arrow gets off before the EHP's Finger of Death spell, but it breaks down once we have monsters with no stats. So if a Hobbit is fighting a Manticora, does the plucky hero throw his stone before the creature's tail spikes fire? We don't have a Dexterity score for the monster. Also, this doesn't specify whether it factors into melee at all.

But I like the idea that Dexterity should impact on initiative. Now our goal is twofold: a spear should get first action over a sword, and Dexterity should impact on initiative.

In the 1975 article in The Strategic Review, "Questions Frequently Asked About Dungeons & Dragons Rules," Gygax did make some attempt to clarify initiative:

Initiative is always checked. Surprise naturally allows first attack in many cases. Initiative thereafter is simply a matter of rolling two dice (assuming that is the number of combatants) with the higher score gaining first attack that round. Dice scores are adjusted for dexterity and so on.This doesn't specify exactly how Dexterity adjusts initiative, but in the ensuing example Gygax says that the Hero gets a bonus of 1 due to high Dexterity. We can reasonably extrapolate that he is geting +1 for a Dexterity of 13 or better, matching the missile adjustments given in OD&D.

Unfortunately the method in the OD&D FAQ doesn't get us an effect much like that in Chainmail. Now initiative is mostly random, with a bump for Dexterity, but weapon length has disappeared from the equation.

The Judges Guild tried to solve all these factors (and add a few more) in the Ready Ref Sheets. The Weapon Priority table (you can see it on the Zenopus Archives site here) factors in weapon length, spell level, missile weapons, dragon breath weapons, armor, monster speed and Dexterity. Which is all for the good, except that the priority system has a fatal flaw: it makes longer weapons better in absolute terms than shorter ones. A spear in these rules is better than a sword, and if you're using all d6 damage, there's no reason to ever use a sword. Which is silly, as there are plenty of reasons to use swords in real life.

This really only works if you can work out in advance that, say, a fighting-man in plate with a sword and Dexterity of 14 has a total rating of 5, while an orc (9" move) with a spear has 6. The orc always goes first. But it has some good ideas, and we can pull this all together without so much work that it's unwieldy.

This is a much-simplified table that takes into account weapon length:

| Factor | Round 1 | Rounds 2+ |

| Long Weapon* | +1 | n/a |

| Short Weapon** | -1 | n/a |

| Dexterity/Move 8 or less | -1 | -1 |

| Dexterity/Move 13 or higher | +1 | +1 |

| Encumbered (Moving at 1/2 speed) | -1 | -1 |

* Morning Star, Flail, Spear, Pole Arm, Halberd, 2-handed Sword, Lance, Pike

** Dagger, Hand Axe, Mace

The system is simple: roll initiative on 1d6, individual for PCs, as a group for monsters, and apply the above modifiers. Roll-off (no modifiers) on ties.

I chose not to flip the modifiers after round 1. Particularly in d6-based damage systems, 2-handed weapons don't have a large advantage, and giving them a penalty for most of the fight makes them nearly useless. I also threw in the encumbered modifier from the Ready Ref Sheets rule, and merged Dexterity and monster Move rates, which are pretty similar.

This does pretty much everything I want an initiative system to do: it takes into account weapon length, but only on the first round, it takes Dexterity into account, and it makes movement rates a bigger part of the game. A dextrous, light-armored fighting-man with a spear (+3) is at a pretty big advantage versus a clumsy, heavily encumbered cleric with a mace (-3), and will almost certainly get the jump on him.

Saturday, December 6, 2014

OD&D Hobbits, Scouting and Light

A while back a story of mine encouraged a post over on the Zenopus Archives saying Hobbits are the Rangers of Basic D&D. Looking through Chainmail recently, I noticed a bit that Zach also quoted:

But it occurs to me that hobbits are also very natural dungeoneers. Which led me to look at The Hobbit, and specifically its description of Frodo's experience while underground.

OD&D is stingier with regard to infravision and darkvision than its descendants; elves and dwarves don't get it any more than humans or hobbits. And lacking thieves, but giving all demihumans enhanced chances to hear, I think hobbits doing dungeon scouting becomes a natural fit. Keep in mind that hobbits are excellent at hiding and will do so quite naturally.

In running dungeon-based games over the years in many systems, it's always seemed like this is an irritating point. Unless you send a dwarf or an elf ahead, or are high enough level to throw around Infravision spells, the natural scouts – B/X human thieves, AD&D halfling thieves, OD&D hobbits – always run into this problem where their natural scouting abilities are limited by inability to see in the dark. Once you're sending a torch ahead, the group typically decides to do reconnaissance in force, sending the whole party in formation through the dungeon and leading to a "kill everything" mentality. And in original and classic D&D that's a recipe for TPKs.

Giving OD&D hobbits the ability to navigate by sound, touch, and instinct (but not to see in the dark; they may have a feeling that something is in a chamber but not know what's there) goes a long way toward solving this practical problem. Obviously they won't be able to do intricate maps, but counting the number of side passages and knowing the navigation paths leading to the next set of stairs allows a PC party to make much better decisions about the way they're going than simply having them lump from room to room like drunken sailors.

Obviously when PCs get infravision they become the natural scouts, replacing the need for such hobbitry. But as a method for OD&D, I would think this is a very viable replacement for the thief-as-blind-scout.

Remember that they are able to blend into the background and so make excellent scouts.OD&D's hobbits are low in utility; they only get to 4th level, have good saving throws (+4 to level), and are "deadly accurate" with missiles, which should mean roughly that hobbits can throw stones with a bonus on the to-hit table. I would consider adjudicating this the same way that OD&D adjusts the saving throws for dwarves and hobbits, giving them a shift upward in level (so starting at 5th level and going up to 9th) for the column used on Attack Matrix 1.

But it occurs to me that hobbits are also very natural dungeoneers. Which led me to look at The Hobbit, and specifically its description of Frodo's experience while underground.

Hobbits are not quite like ordinary people; and after all if their holes are nice cheery places and properly aired, quite different from the tunnels of the goblins, still they are more used to tunnelling than we are, and they do not easily lose their sense of direction underground – not when their heads have recovered from being bumped. Also they can move very quietly, and hide easily, and recover wonderfully from falls and bruises ...The light from Sting is mentioned repeatedly in the sojourn that follows, but what is really intriguing is that Bilbo mostly finds his way through the goblin caves by instinct and feel, only to be surprised when he finally hits the underground lake in Gollum's lair.

OD&D is stingier with regard to infravision and darkvision than its descendants; elves and dwarves don't get it any more than humans or hobbits. And lacking thieves, but giving all demihumans enhanced chances to hear, I think hobbits doing dungeon scouting becomes a natural fit. Keep in mind that hobbits are excellent at hiding and will do so quite naturally.

In running dungeon-based games over the years in many systems, it's always seemed like this is an irritating point. Unless you send a dwarf or an elf ahead, or are high enough level to throw around Infravision spells, the natural scouts – B/X human thieves, AD&D halfling thieves, OD&D hobbits – always run into this problem where their natural scouting abilities are limited by inability to see in the dark. Once you're sending a torch ahead, the group typically decides to do reconnaissance in force, sending the whole party in formation through the dungeon and leading to a "kill everything" mentality. And in original and classic D&D that's a recipe for TPKs.

Giving OD&D hobbits the ability to navigate by sound, touch, and instinct (but not to see in the dark; they may have a feeling that something is in a chamber but not know what's there) goes a long way toward solving this practical problem. Obviously they won't be able to do intricate maps, but counting the number of side passages and knowing the navigation paths leading to the next set of stairs allows a PC party to make much better decisions about the way they're going than simply having them lump from room to room like drunken sailors.

Obviously when PCs get infravision they become the natural scouts, replacing the need for such hobbitry. But as a method for OD&D, I would think this is a very viable replacement for the thief-as-blind-scout.

Monday, November 17, 2014

A Missing Link: A Miniature Megadungeon

(A brief edit to note: This is officially my 300th post on this blog. Wow.)

Zach Howard at the Zenopus Archives has managed to surprise us again, this time showing the original cross-section of Holmes's sample dungeon. Take a look and come back, I'll be talking about the hand-drawn image a good bit.

This little diagram is a master class in the "megadungeon in miniature." It condenses into 3 levels most of the principal ideas that underlie the Gygaxian megadungeon. There are multiple entrances, multiple connections between levels, different types of terrain, sloping passages, and generally everything you'd want from a complex dungeon, all in three neat levels. None of which is to disregard Tom Wham's great Skull Mountain diagram, but Holmes manages to do a lot with a few levels.

We come to two entrances on separate hills. This creates an interesting choice right off the bat. There might be something low-level like goblins or kobolds guarding the hillside entrance, but the descent into the mine is obviously the deeper way down. It's a good idea to let the rumor tables give a hint that the mine shaft to level 2 is a way down to more difficult monsters than the hillside cave.

In level 1 we're about equidistant from the two ways down. The level below the ladder has one of the long, gradual slopes that Gygax was fond of, and a party may reasonably be surprised when they go up a level of stairs and are still on the second level. Holmes's original wandering monster tables, drawn from Supplement I: Greyhawk, might give us a good idea of what kinds of threats lurk in each of them. Given how many humans with levels there are, it either suggests that the dungeon has a significant human faction, or is actively plied by rival adventuring parties. Either choice is interesting.

I really love those two carved-out areas by the mine shaft. They just have a ton of potential for mischief. As soon as I saw them I was envisioning a nasty monster swooping out as the PCs try to go down (or up) the ladder and causing all kinds of havoc. Or they could be rooms that are rigged with nasty traps, maybe something explosive, or a simple arrow trap that happens to knock the PC a long way down to the dungeon floor below. Or one of them could have a treasure visible, but a monster or a trap nearby that will turn the PCs' avarice into their undoing.

The third level's relative size suggests it should be a nice, big, sprawling level with lots of rooms and interesting tricks. Then there's the cave, and I have to admit if it had a lake indicated it'd be exactly after my heart. As it stands, the cave feels like it should really be the lair of a dragon as the culmination of the whole adventure (and a justification for the game being "Dungeons & Dragons"). It would really make the whole thing a summation of D&D in three levels.

It doesn't have the domed city and the great stone skull of Wham's drawing, but Holmes's original sketch points to a dungeon that can be played in the three character levels suggested by his rule book, and still give you the megadungeon experience. There's no reason the weird and cool stuff we've talked about previously can't be on these three levels, and Wham's drawing really only gives us an extra two or three true "levels" (counting 2 and 2A, the entrance cave as "one up", and the cave separate from the third normal dungeon level). What I think using a dungeon like this does is gives just enough of the complex elements without going into "megadungeon fatigue" that modern games often run into. By the time the players are bored with runs into the same dungeon, they're finished.

From that perspective, this is the missing link between the megadungeon and the smaller types that came to dominate the scene after the mid-1970s. You could describe this in a relatively short module but have months of play material come out of it. The only published dungeon that really comes close to this is Caverns of Thracia, whose reputation should tell you how great of a dungeon I think this could be turned into.

Zach Howard at the Zenopus Archives has managed to surprise us again, this time showing the original cross-section of Holmes's sample dungeon. Take a look and come back, I'll be talking about the hand-drawn image a good bit.

This little diagram is a master class in the "megadungeon in miniature." It condenses into 3 levels most of the principal ideas that underlie the Gygaxian megadungeon. There are multiple entrances, multiple connections between levels, different types of terrain, sloping passages, and generally everything you'd want from a complex dungeon, all in three neat levels. None of which is to disregard Tom Wham's great Skull Mountain diagram, but Holmes manages to do a lot with a few levels.

We come to two entrances on separate hills. This creates an interesting choice right off the bat. There might be something low-level like goblins or kobolds guarding the hillside entrance, but the descent into the mine is obviously the deeper way down. It's a good idea to let the rumor tables give a hint that the mine shaft to level 2 is a way down to more difficult monsters than the hillside cave.

In level 1 we're about equidistant from the two ways down. The level below the ladder has one of the long, gradual slopes that Gygax was fond of, and a party may reasonably be surprised when they go up a level of stairs and are still on the second level. Holmes's original wandering monster tables, drawn from Supplement I: Greyhawk, might give us a good idea of what kinds of threats lurk in each of them. Given how many humans with levels there are, it either suggests that the dungeon has a significant human faction, or is actively plied by rival adventuring parties. Either choice is interesting.

I really love those two carved-out areas by the mine shaft. They just have a ton of potential for mischief. As soon as I saw them I was envisioning a nasty monster swooping out as the PCs try to go down (or up) the ladder and causing all kinds of havoc. Or they could be rooms that are rigged with nasty traps, maybe something explosive, or a simple arrow trap that happens to knock the PC a long way down to the dungeon floor below. Or one of them could have a treasure visible, but a monster or a trap nearby that will turn the PCs' avarice into their undoing.

The third level's relative size suggests it should be a nice, big, sprawling level with lots of rooms and interesting tricks. Then there's the cave, and I have to admit if it had a lake indicated it'd be exactly after my heart. As it stands, the cave feels like it should really be the lair of a dragon as the culmination of the whole adventure (and a justification for the game being "Dungeons & Dragons"). It would really make the whole thing a summation of D&D in three levels.

It doesn't have the domed city and the great stone skull of Wham's drawing, but Holmes's original sketch points to a dungeon that can be played in the three character levels suggested by his rule book, and still give you the megadungeon experience. There's no reason the weird and cool stuff we've talked about previously can't be on these three levels, and Wham's drawing really only gives us an extra two or three true "levels" (counting 2 and 2A, the entrance cave as "one up", and the cave separate from the third normal dungeon level). What I think using a dungeon like this does is gives just enough of the complex elements without going into "megadungeon fatigue" that modern games often run into. By the time the players are bored with runs into the same dungeon, they're finished.

From that perspective, this is the missing link between the megadungeon and the smaller types that came to dominate the scene after the mid-1970s. You could describe this in a relatively short module but have months of play material come out of it. The only published dungeon that really comes close to this is Caverns of Thracia, whose reputation should tell you how great of a dungeon I think this could be turned into.

Labels:

dungeons,

holmes,

megadungeons,

zenopus archives rocks

Friday, November 14, 2014

Percent Liar

(That's Lying Cat, familiar to fans of the comic Saga.)

I was looking at Arduin for a completely different post idea, and it always brings me back to the funniest statistic in that book: % Liar. Early printings of OD&D put this instead of % Lair. Rather than go along with the errata, Dave Hargrave made this a statistic of its own. The Air Shark, the first monster in the list, has a % Liar of "Too stupid to." And that, my friends, is Retro Stupid.

But % Liar is an interesting idea for a social mechanic (the kind of thing people always say OD&D doesn't have, even though it does). It fits with the aleatoric approach to the game, where random chance is allowed to determine certain key factors. Having a % chance that a monster will lie to you is a perfectly reasonable mechanic given the way that Contact Higher Plane has a veracity percentage to determine whether the result is true or not.

What interests me is that it creates an expectation that some monsters will be more trustworthy than others. Say a goblin has a 50% liar rating while a gnoll has a 30% rating (using the actual % Lair column just for a moment). The trustworthiness of the gnoll is an interesting bit of setting-building. What is it about gnolls that makes them less likely to lie? They are considerably more reliable than a coin flip, which is what the goblins are, but there's still a real chance that listening to them will land you in hot water sooner or later.

There's even a sort of gambling aspect that could emerge from this; once PCs find a particular monster is fairly reliable, they could try to tap the well just enough, pressing their luck that this won't be the time the liar dice come up against them. The lies can also be subtle twisting of the truth, like the rumor about a trapped maiden in Keep on the Borderlands that is designed to trick PCs into "rescuing" the medusa.

This would work well with a two-column rumor table, where one side is true rumors and the other is false, misleading ones. Say a goblin has a 50% chance to be lying; you can roll it organically. If you roll a 1-10 on a d20, you check the corresponding entries on the "lying" table. If you roll 11-20, you check the "truth" table. Gnolls only check "lying" on 1-6. This lets the referee make the lies more varied; for instance, lies 7-10 might be more outrageous, as creatures prone to lie more often will have a tell. So lying rumor 6 might be that the room beyond the statue is empty, when it's actually an ogre's lair, while lying rumor 10 might say it is a dragon's lair.

NPCs could also have a % Liar. We could base it on their alignment; Lawfuls may only have a 5% chance, while Chaotics could be 40% or higher. In general it seems apt to align the percentage to alignment without getting totally out of hand, thus giving a game use to alignment aside from the ever-controversial alignment languages.

Obviously this system places a bit more of a premium on magic and items that help to detect lies versus truth. Finding out about the reputation of various creature types is also a highly useful piece of knowledge, as detailed above. If players know that it is more useful to negotiate with gnolls than goblins, it adds a new strategic dimension when they encounter the more "honest" creature type to parley instead of fighting.

Sure it's a typo, but why not ride it out and add an interesting dimension to D&D?

I was looking at Arduin for a completely different post idea, and it always brings me back to the funniest statistic in that book: % Liar. Early printings of OD&D put this instead of % Lair. Rather than go along with the errata, Dave Hargrave made this a statistic of its own. The Air Shark, the first monster in the list, has a % Liar of "Too stupid to." And that, my friends, is Retro Stupid.

But % Liar is an interesting idea for a social mechanic (the kind of thing people always say OD&D doesn't have, even though it does). It fits with the aleatoric approach to the game, where random chance is allowed to determine certain key factors. Having a % chance that a monster will lie to you is a perfectly reasonable mechanic given the way that Contact Higher Plane has a veracity percentage to determine whether the result is true or not.

What interests me is that it creates an expectation that some monsters will be more trustworthy than others. Say a goblin has a 50% liar rating while a gnoll has a 30% rating (using the actual % Lair column just for a moment). The trustworthiness of the gnoll is an interesting bit of setting-building. What is it about gnolls that makes them less likely to lie? They are considerably more reliable than a coin flip, which is what the goblins are, but there's still a real chance that listening to them will land you in hot water sooner or later.

There's even a sort of gambling aspect that could emerge from this; once PCs find a particular monster is fairly reliable, they could try to tap the well just enough, pressing their luck that this won't be the time the liar dice come up against them. The lies can also be subtle twisting of the truth, like the rumor about a trapped maiden in Keep on the Borderlands that is designed to trick PCs into "rescuing" the medusa.

This would work well with a two-column rumor table, where one side is true rumors and the other is false, misleading ones. Say a goblin has a 50% chance to be lying; you can roll it organically. If you roll a 1-10 on a d20, you check the corresponding entries on the "lying" table. If you roll 11-20, you check the "truth" table. Gnolls only check "lying" on 1-6. This lets the referee make the lies more varied; for instance, lies 7-10 might be more outrageous, as creatures prone to lie more often will have a tell. So lying rumor 6 might be that the room beyond the statue is empty, when it's actually an ogre's lair, while lying rumor 10 might say it is a dragon's lair.

NPCs could also have a % Liar. We could base it on their alignment; Lawfuls may only have a 5% chance, while Chaotics could be 40% or higher. In general it seems apt to align the percentage to alignment without getting totally out of hand, thus giving a game use to alignment aside from the ever-controversial alignment languages.

Obviously this system places a bit more of a premium on magic and items that help to detect lies versus truth. Finding out about the reputation of various creature types is also a highly useful piece of knowledge, as detailed above. If players know that it is more useful to negotiate with gnolls than goblins, it adds a new strategic dimension when they encounter the more "honest" creature type to parley instead of fighting.

Sure it's a typo, but why not ride it out and add an interesting dimension to D&D?

Wednesday, October 8, 2014

Diplomacy, D&D and Roleplaying

If you've never read it, it's worth going through Mike Mornard's question & answer thread on the OD&D forum - Klytus, I'm bored. Not just because I asked a bunch of the questions, but generally because it gives a good feel for how D&D worked when Gary ran it.

When I asked Mike about Diplomacy, he responded with this:

When you consider that many of the pioneering roleplayers were Diplomacy players, their style of roleplaying becomes much clearer. As I said in my last post, negotiation is a key aspect of dungeoneering in early editions as written, but was all too often overlooked in favor of the expedient of simply fighting.

The best evidence of this is B2 Keep on the Borderlands. Here is a scenario right out of the many Diplomacy variants: each humanoid group has its forces, every group can pretty easily kill the PCs, but with careful negotiation they can play one against the other. You could run an interesting Diplomacy-type game where each player takes the role of one of the faction leaders and tries to take on the other groups. There's also the cleric and his followers, who go along with the "backstabbing hireling" motif that we saw in "The Magician's Ring."

There's a tendency, particularly in America, to see diplomacy as something "soft," something you resort to when you can't get your way by brute force. Gygax had a keen sense for it, though, and understood it much better. I'm reminded of a podcast where Dan Carlin talked about how the ancient Romans viewed diplomacy as an offensive weapon. Done properly, you can disorient or even eliminate enemies without fighting them yourself.

I think this view of roleplaying has a lot to offer. If you play old school D&D as written, with the reaction table and hireling loyalty and so on, elements of it will come out naturally. And it offers a fun, playable alternative to people who think of role-playing primarily in terms of melodramatic play-acting.

When I asked Mike about Diplomacy, he responded with this:

I played a bit of Diplomacy. More importantly, though, Gary and some of the others played a LOT. It shows in the role playing system of OD&D. There are those who say "there was no role playing in OD&D because there are no rules for DIPLOMACY or BLUFF or INTIMIDATE," etc. But in fact it was full of role playing and negotiation, just like Diplomacy. And like Diplomacy, if you wanted to Bluff, you BLUFFED. If you wanted to make a deal, you MADE A DEAL. Et cetera.Later in the thread, he describes Gygax's NPCs:

Pretty much everybody. If you search online you can find Gary's story "The Magician's Ring." "Lessnard" is me, and yeah, that happened. That was pretty typical... his NPCs were greedy and opportunisitc to a fault.You can find "The Magician's Ring" at Greyhawk Grognard, and it's as Mike describes. Now, I want to posit that the two quotes above are intimately linked. Diplomacy is a game that is infamous for its maneuvering and treachery, where making deals and then stabbing a partner in the back are the best strategy to win.

Then you had more mundane stuff like blacksmiths covering swords with luminous paint and selling them as magic swords, and "angry villagers" keeping you from getting your money back.

Truthfully, his NPCs went beyond "will screw you if it profits them" to "will screw you unless not doing so profits them a lot."

When you consider that many of the pioneering roleplayers were Diplomacy players, their style of roleplaying becomes much clearer. As I said in my last post, negotiation is a key aspect of dungeoneering in early editions as written, but was all too often overlooked in favor of the expedient of simply fighting.

The best evidence of this is B2 Keep on the Borderlands. Here is a scenario right out of the many Diplomacy variants: each humanoid group has its forces, every group can pretty easily kill the PCs, but with careful negotiation they can play one against the other. You could run an interesting Diplomacy-type game where each player takes the role of one of the faction leaders and tries to take on the other groups. There's also the cleric and his followers, who go along with the "backstabbing hireling" motif that we saw in "The Magician's Ring."

There's a tendency, particularly in America, to see diplomacy as something "soft," something you resort to when you can't get your way by brute force. Gygax had a keen sense for it, though, and understood it much better. I'm reminded of a podcast where Dan Carlin talked about how the ancient Romans viewed diplomacy as an offensive weapon. Done properly, you can disorient or even eliminate enemies without fighting them yourself.

I think this view of roleplaying has a lot to offer. If you play old school D&D as written, with the reaction table and hireling loyalty and so on, elements of it will come out naturally. And it offers a fun, playable alternative to people who think of role-playing primarily in terms of melodramatic play-acting.

Monday, October 6, 2014

What are D&D and the OSR? - A Couple of Reactions

A couple of quotes have made me want to write a kneejerk reaction. I don't like blogging from kneejerks but I think these make some good places to hang points I'd like to make.

John Wick said some dumb things in a blog post. But one of them is actually worth responding to.

But I'm going to submit that Holmes D&D – which definitely fits in the "first four editions" – is actually a really good roleplaying game, by Wick's criteria. You see, Holmes wrote on page 11 that monsters don't necessarily attack, but instead reactions should be determined on the reaction chart lifted from OD&D. Strictly speaking, this chart in OD&D is used to determine monster reactions to an offer made by the PCs, but Holmes changes it so that it refers directly to encounter reactions. This means that some monsters encountered in the Holmes edition of the game will be "friendly" and involve some negotiation. If the referee chooses to ignore that, it's not the D&D game's fault; it told the players to roleplay, right there in the text.

In fact, I would submit that this makes D&D a really good roleplaying game. Roleplaying is not just play-acting your character; it's negotiation as part of a strategy for surviving in a ridiculously lethal dungeon and getting out with treasure. By the book, in Holmes D&D, roleplaying is a required part of the game and, in fact, is a really good strategy. If you keep negotiating there is a 50/50 chance that you will get a positive result. The worst thing that can happen is that you're forced to fight.

Did people play D&D that way? A lot of them didn't. But a lot of people don't play Monopoly by the rules, either. It's just what happens when you have a really popular game. But D&D is distinctly a roleplaying game, even if you don't play it that way.

Then there's Ron Edwards, who makes a wonderful flamebait comment in an interview on the Argentine blog Runas Explosivas.

The marketing aspect is interesting. I almost want to agree with it, in that it's primarily a label for people and products to denote that they are oriented to the "old school," but I disagree with its cynicism. The community aspect of the OSR, from blogs to G+ and the associated forums, has been probably more important overall than the marketing. You can bicker and argue over whether it's one single thing or a lot of things, but what you can't argue is that there are a lot of people in a network creating and consuming content.

Honestly the rest of Ron's interview isn't really worth much response. The OSR isn't that close to most Forge stuff when you get down to brass tacks. What happens in the game play experience is simply too different. Back in his heyday, Ron called the classic era of D&D a period of cargo cults, while I find it to have been far more creative and unrestrained. (That essay also contains his total misunderstanding of Gygax and Arneson, and application of the "Big Model" to their D&D.)

It's unfortunate, after eight years of doing this, that we are still at a high point of misunderstanding old school D&D from people who ought to know better. I've always found that the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and old school D&D is a real thing, and in the OSR period it's been great roleplaying.

John Wick said some dumb things in a blog post. But one of them is actually worth responding to.

The first four editions of D&D are not roleplaying games. You can successfully play them without roleplaying.Which of course is nonsense. The term "role-playing game" was invented by people trying to describe what happened when they were playing Dungeons & Dragons. Any definition which doesn't include D&D is, prima facie, wrong.

But I'm going to submit that Holmes D&D – which definitely fits in the "first four editions" – is actually a really good roleplaying game, by Wick's criteria. You see, Holmes wrote on page 11 that monsters don't necessarily attack, but instead reactions should be determined on the reaction chart lifted from OD&D. Strictly speaking, this chart in OD&D is used to determine monster reactions to an offer made by the PCs, but Holmes changes it so that it refers directly to encounter reactions. This means that some monsters encountered in the Holmes edition of the game will be "friendly" and involve some negotiation. If the referee chooses to ignore that, it's not the D&D game's fault; it told the players to roleplay, right there in the text.

In fact, I would submit that this makes D&D a really good roleplaying game. Roleplaying is not just play-acting your character; it's negotiation as part of a strategy for surviving in a ridiculously lethal dungeon and getting out with treasure. By the book, in Holmes D&D, roleplaying is a required part of the game and, in fact, is a really good strategy. If you keep negotiating there is a 50/50 chance that you will get a positive result. The worst thing that can happen is that you're forced to fight.

Did people play D&D that way? A lot of them didn't. But a lot of people don't play Monopoly by the rules, either. It's just what happens when you have a really popular game. But D&D is distinctly a roleplaying game, even if you don't play it that way.

Then there's Ron Edwards, who makes a wonderful flamebait comment in an interview on the Argentine blog Runas Explosivas.

"Old school" is a marketing term and is neither old nor an identifiable single way to play (school).In his novel Bleak House, Charles Dickens pithily described his use of old school as "a phrase generally meaning any school that seems never to have been young." It's part of why old school gaming has always been somewhat associated with the grognards, named after Napoleon's veterans who were infamous for grumbling, even to l'Empereur himself. People misunderstand "old school" to mean "the way that people played back in 197x or 198x" when it really means a re-emphasizing of certain "classic" tropes and ideas, including adventure design, mechanics, and play style.

The marketing aspect is interesting. I almost want to agree with it, in that it's primarily a label for people and products to denote that they are oriented to the "old school," but I disagree with its cynicism. The community aspect of the OSR, from blogs to G+ and the associated forums, has been probably more important overall than the marketing. You can bicker and argue over whether it's one single thing or a lot of things, but what you can't argue is that there are a lot of people in a network creating and consuming content.

Honestly the rest of Ron's interview isn't really worth much response. The OSR isn't that close to most Forge stuff when you get down to brass tacks. What happens in the game play experience is simply too different. Back in his heyday, Ron called the classic era of D&D a period of cargo cults, while I find it to have been far more creative and unrestrained. (That essay also contains his total misunderstanding of Gygax and Arneson, and application of the "Big Model" to their D&D.)

It's unfortunate, after eight years of doing this, that we are still at a high point of misunderstanding old school D&D from people who ought to know better. I've always found that the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and old school D&D is a real thing, and in the OSR period it's been great roleplaying.

Labels:

holmes,

old school renaissance,

philosophy,

reaction tables

Saturday, September 27, 2014

Two Copper Pieces on OSR History

Erik Tenkar has been writing guides to the OSR games out there. For his trouble, he's being accused of historical revisionism by the "RPG Pundit," a person who you may remember from "consultant-gate." Erik's post about it is here. I won't link to the Pundit's site but you can find the post by Googling his pseudonym.

The attack on Tenkar is based on the idea that the early / close retro-clones weren't really the font from which the old school renaissance came. Which is malarkey. The OSR became a single thing in 2009, when Dan Proctor made it one.

A history of the OSR can start in dozens of places. You can start in Dragonsfoot, with gamers who never really stopped playing AD&D or B/X D&D getting together to talk shop. Or you can start with Hackmaster, which put 1e back into print (albeit in a strangely modified form). Or with Castles & Crusades, which created a lot of the pressure for these games. Or you could look at Necromancer Games with its "First Edition Feel" and 3e reprints of Judges Guild products, or Goodman Games's Dungeon Crawl Classics series. Or you could look at WotC's early PDF releases, which included OD&D for a hot minute.

There were literally dozens of things contributing to an old school explosion in the mid-2000s. The RPG Pundit bizarrely chooses to look at two oddball projects. One, Mazes & Minotaurs, was an attempt to imagine what D&D might have been like with an ancient Greek flavor. The other, Encounter Critical, was an attempt to pawn off a fake late '70s RPG. EC has had some influence on the OSR, because Jeff Rients loves the thing. But I've never detected any real influence coming from M&M, and as someone who minored in ancient Greek and Roman history in college, I would be able to tell.

The problem with looking at it from the influences is that events like the OSR are not unitary things. No single event happened and then the OSR was on; it was more that several things were happening in parallel, and they only happened to be grouped together later. The old school buildup wasn't a single powder keg; it was several smaller fires that later merged, and later still drifted apart in ways.

But the most important events were the publication of BFRPG and OSRIC, because they changed things fundamentally. Once BFRPG and AA#1 Pod-Caverns of the Sinister Shroom were in print, there were now rules and adventures resembling those of the late 1970s and early 1980s, with no apologies, no parody elements, no conversion to 3e or a "modernized" system. RPG products that were old school as a badge of pride.

OSRIC and BFRPG were fundamentally different. OSRIC was something of a fig-leaf, a system designed to be indistinguishable from AD&D so that you could use modules for OSRIC with your AD&D books with no conversion. There was no assuption that people would play OSRIC; in fact, there were at least 20 modules released before it was available in print. BFRPG, by contrast, was a community project meant to be played, B/X with a light clean-up to a few rules.

What was important was that the barrier was breached in the summer of 2006, and that's when the flood of material that we can now identify as part of the OSR started to happen. The Hoard & Horde spreadsheet by Guy Fullerton makes it abundantly clear that things changed significantly at that exact point in time. Any history that doesn't frankly say that before BFRPG and OSRIC there wasn't what we identify today as OSR publication, and afterward there is, is being revisionist.

The derisive mentions of "clone-mania" and "Talmudic" interpretation of rules and Gygaxian minutiae make it quite clear what the Pundit's revisionist agenda is. He doesn't like the wing of the OSR represented by that play style, that sticks close to the old games instead of remixing them and re-imagining them. Ironically this misses a big chunk of the point of OSRIC and BFRPG, which has always been to get adventures and support material out there for these older systems. There are three hardback collections on my shelf of Advanced Adventures collections; each contains 10 complete OSRIC modules. BFRPG just released a book of adventures in print. Neither gives much of a damn about history or precise accuracy.

BFRPG wanted to get people playing old school B/X style games again, and it succeeded. OSRIC wanted to get new support material for original AD&D, and it succeeded. These are admirable goals, rooted in actual play and the continuity of a gaming community that are worthwhile in themselves. The OSR should be proud to say these games are where our prehistory ends and our history begins.

The attack on Tenkar is based on the idea that the early / close retro-clones weren't really the font from which the old school renaissance came. Which is malarkey. The OSR became a single thing in 2009, when Dan Proctor made it one.

A history of the OSR can start in dozens of places. You can start in Dragonsfoot, with gamers who never really stopped playing AD&D or B/X D&D getting together to talk shop. Or you can start with Hackmaster, which put 1e back into print (albeit in a strangely modified form). Or with Castles & Crusades, which created a lot of the pressure for these games. Or you could look at Necromancer Games with its "First Edition Feel" and 3e reprints of Judges Guild products, or Goodman Games's Dungeon Crawl Classics series. Or you could look at WotC's early PDF releases, which included OD&D for a hot minute.

There were literally dozens of things contributing to an old school explosion in the mid-2000s. The RPG Pundit bizarrely chooses to look at two oddball projects. One, Mazes & Minotaurs, was an attempt to imagine what D&D might have been like with an ancient Greek flavor. The other, Encounter Critical, was an attempt to pawn off a fake late '70s RPG. EC has had some influence on the OSR, because Jeff Rients loves the thing. But I've never detected any real influence coming from M&M, and as someone who minored in ancient Greek and Roman history in college, I would be able to tell.

The problem with looking at it from the influences is that events like the OSR are not unitary things. No single event happened and then the OSR was on; it was more that several things were happening in parallel, and they only happened to be grouped together later. The old school buildup wasn't a single powder keg; it was several smaller fires that later merged, and later still drifted apart in ways.

But the most important events were the publication of BFRPG and OSRIC, because they changed things fundamentally. Once BFRPG and AA#1 Pod-Caverns of the Sinister Shroom were in print, there were now rules and adventures resembling those of the late 1970s and early 1980s, with no apologies, no parody elements, no conversion to 3e or a "modernized" system. RPG products that were old school as a badge of pride.

OSRIC and BFRPG were fundamentally different. OSRIC was something of a fig-leaf, a system designed to be indistinguishable from AD&D so that you could use modules for OSRIC with your AD&D books with no conversion. There was no assuption that people would play OSRIC; in fact, there were at least 20 modules released before it was available in print. BFRPG, by contrast, was a community project meant to be played, B/X with a light clean-up to a few rules.

What was important was that the barrier was breached in the summer of 2006, and that's when the flood of material that we can now identify as part of the OSR started to happen. The Hoard & Horde spreadsheet by Guy Fullerton makes it abundantly clear that things changed significantly at that exact point in time. Any history that doesn't frankly say that before BFRPG and OSRIC there wasn't what we identify today as OSR publication, and afterward there is, is being revisionist.

The derisive mentions of "clone-mania" and "Talmudic" interpretation of rules and Gygaxian minutiae make it quite clear what the Pundit's revisionist agenda is. He doesn't like the wing of the OSR represented by that play style, that sticks close to the old games instead of remixing them and re-imagining them. Ironically this misses a big chunk of the point of OSRIC and BFRPG, which has always been to get adventures and support material out there for these older systems. There are three hardback collections on my shelf of Advanced Adventures collections; each contains 10 complete OSRIC modules. BFRPG just released a book of adventures in print. Neither gives much of a damn about history or precise accuracy.

BFRPG wanted to get people playing old school B/X style games again, and it succeeded. OSRIC wanted to get new support material for original AD&D, and it succeeded. These are admirable goals, rooted in actual play and the continuity of a gaming community that are worthwhile in themselves. The OSR should be proud to say these games are where our prehistory ends and our history begins.

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

On the Buying and Selling of Magic

(A small note: Apologies about my prolonged dearth of posts. I simply haven't had a mix of time and blog-worthy posts in a while. I'm gearing up for some things and hopefully that changes in the not too distant future.)

I wrote briefly in the past about dungeon markets. Erik Tenkar today asked about magic shops and I think that the question deserves a bit of exploration.

On a gut-check level, the idea of a magic item store is revolting to me. The thought that you can walk into a store, lay down gold, and buy a magical sword that fits exactly what you need goes against everything I actually like about fantasy gaming. Magic items ought to be rare, treasure, hoarded and not given up lightly. And that really governs the question for me. But the proliferation of items in D&D modules does raise a need for some economy of the things.

As I've mulled it over, I think my objection to magic item shops is really an objection to making procuring magic items something that is simple, safe and reliable. You should not be able to walk into a store, lay down your money, and walk out with a Sword +3, Frost Brand as easily as buying a pair of boots. I'd say at minimum, two of the three elements of safe, simple and reliable should be removed from the equation.

The Troll Market approach I outlined previously is a good way to take away the safe element. Magic items are not necessarily being bought and sold in the safe parts of a well-off town. They are being sold by disreputable humans, or even by monsters straight-up. (This is a good excuse for why so many monsters in modules have magic items that they're not actually using – can't damage the goods.) PCs are not necessarily safe, or require certain difficult conditions to avoid violence. This can also remove the simple element, since the market will not always be there at the PCs' leisure. It could move, and require new challenges to find again. I really like the idea of some of this taking on a sort of "black market" vibe.

Reliability is trivially easy to fix: with magic, there are no guarantees. Sure, the sword shows up as magical when you cast detect magic, but how do you know whether it has the purported properties? It could be cursed, or it could be substantially different. Unless you're willing to blow a charge, how are you certain that the item is a Wand of Fireballs? And it's a very dangerous proposition to test even if you are willing.

Simplicity can be adjusted by making it very difficult to find a specific type of item. Sure, you can grab a Potion of Healing from a high-end alchemist/wizard, and you might be able to track down Arrows +1 if you know where to look, but it should be a lot more of a pain to find a Sword +1, +3 against Dragons. Even if you buy into the magic item economy idea, that doesn't mean that absolutely anything is available easily. And like anything a PC is trying to find, specific items make for terrific adventure seeds.

Another factor to consider in all of this is how magic items react to each other. Having a lot of magic items in one place might not be a completely safe proposition. Too much magic could mean that a magic-item bazaar might create a wild magic area, where spell effects happen entirely at random, and it's dangerous to Detect Magic or Identify, causing havoc with reliability. A store that had every type of magical sword and potion available might run into reasons to roll, say, on the 1e DMG's potion miscibility table, or problems when two intelligent swords decide they don't like each other.

Of course, you can solve all of that by just saying "no" when players want to do buying and selling of magic items. But if you decide to run with it, I think all kinds of interesting problems can be created. Just don't make it simple, safe and reliable.

I wrote briefly in the past about dungeon markets. Erik Tenkar today asked about magic shops and I think that the question deserves a bit of exploration.